Combat Sports Strength and Conditioning - Microcycle & Within-Session Programming [Part 2 of Programming Layers Series]

In part 2 of this article series, we’ll discuss principles and training methodologies that can be used to optimize combat sports training within-session and within the week.

Given the complexities of combat sports performance, strength and conditioning programming must match the demands of the training environment by being adaptable and holistic. In order to achieve this, programming must consider all layers and timelines of training.

Programming and training periodization happens on 4 time scales (or layers) - Within session, on the microcyclic scale, mesocyclic scale and the macrocyclic scale. Each layer can be considered the lenses of which the S&C coach views training and physical preparation and must be planned accordingly.

In this article, we’ll discuss several strategies and philosophies I use when preparing combat sport athletes, which layers they can be utilized in and how a better understanding of programming can help us more effectively coach high performance combat sport athletes.

Some of the concepts I talk about will be familiar to those who have read my eBook “The Strength & Conditioning Handbook for Combat Sports”, while others maybe new to some of you.

In part 2 (this part), we will discuss the specifics week to week and day to day programming (higher resolution view).

Read PART 1 on Macrocyclic and Mesocyclic Training Here

the microcyclic layer

Programming on the microcyclic layer is concerned with optimizing training on the weekly level. Given the amount of sessions in a combat sports athletes’ schedule, we must consolidate them by avoiding any interference effects and create systems that can manage training stressors more consistently. Here are some guiding principles and strategies that you’ll find in my S&C programs.

High/low structure

I use a high/low structure to guide the initial parts of my program planning; a system popularized by track coach Charlie Francis to categorize running intensity and it’s affect on speed adaptations.

“High” training days consists of training modalities that require a large amount of neuromuscular-activation, a large energy expenditure and/or a high cognitive load - all stimuli that require a relatively longer period of full recovery (48-72 hours). Conversely, “low” training days are less neurally, bioenergetically and mentally demanding, requiring a relatively shorter period of full recovery (~24 hours).

Adapted to the world of combat sports, all training modalities, from sparring, technique work, heavy bag training to weight room sessions can all be categorized into high and low. This allows us to visualize the training and recovery demands of sessions throughout a full week of training.

Ideally, we would schedule training so that we alternate high and low training days so that the athlete is adequately rested for the most demanding sessions, but the reality of the fight game makes this challenging in practice. Some sessions, on paper, fall in between high and low categories in terms of physiological load. Regardless, using a high/low structure is a great start to help manage training stress within a week of training.

Condensed conjugate method

First of all, the conjugate method (CM), originally created for powerlifting performance by Louie Simmons of Westside Barbell uses Max Effort (close to 1RM lifting), Dynamic Effort (low % of 1RM performed in high-velocity fashion and Repetition Effort (moderate % of 1RM performed for ~8-15 reps) all within a training week. The CM is based on a concurrent system (I discussed this in part 1, where training aims to develop several physical qualities within a shorter time frame - week and month).

The first time hearing of the condensed conjugate method (CMM) was from Phil Daru, S&C coach to several elite combat sport athletes out in Florida, USA who adapted the CM method to fit the tighter training schedule of fighters.

What is originally a 4-day split (CM) is condensed into 2 days (CMM). This is what the general structure/training split looks like within a week.

Day 1:

Lower Body Dynamic Effort

Upper Body Max Effort

Repetition Effort Focusing On Weaknesses

Day 2:

Upper Body Dynamic Effort

Lower Body Max Effort

Repetition Effort Focusing On Weaknesses

Max effort and dynamic effort training are both performed on the same day, however, to mitigate neuromuscular fatigue, they are rotated based on upper body and lower body lifts. If upper body compound lifts like heavy presses and rows are performed that day (max effort), bounds and jumps will be trained for the lower body to avoid excessive overload.

Similar to most concurrent-based training splits, a large benefit comes from the fact that movements are trained within the whole spectrum of the force-velocity curve (see figure below). Max effort training improves the body’s ability to create maximum amounts of force - grinding strength, while dynamic effort trains the body to be able to produce force at a faster rate - explosive strength/strength. Repetition effort is then used to target weak points and to create structural adaptations like muscle hypertrophy and joint robustness.

The CMM also shares some of the drawbacks of concurrent-based training set-ups. Single athletic qualities progress slower since multiple are being developed at the same time, however, this is only a minor issue considering the mixed demands of many combat sports. Certain modifications can be made to the template or perhaps block periodization can be utilized (see Part 1 of the article) if working with athletes that are clearly force-deficient or velocity-deficient (see the next section on velocity-split). Nonetheless, a pragmatic way to organize both high-velocity and slow-velocity exercises within a training week. I’ve had success implementing this type of training split in my combat sports S&C programs.

Velocity-split

Sticking with the theme of a concurrent-based system within the training week, another way to set up a microcycle is using a velocity-split. For example, in a 2-day training split, high-velocity exercises and low-velocity exercises would be trained separately.

Day 1:

Upper Body Plyometrics & Ballistics

Lower Body Plyometrics & Ballistics

Speed-Strength Exercises (Loaded throws, Olympic Lift deratives, Kettlebell swings, etc)

Day 2:

Upper Body Max Strength Lifts

Lower Body Max Strength Lifts

Repetition Effort Training (70-85% of 1RM)

Isolation Exercises

With concurrent training, we risk pulling an athlete’s physiology in opposite directions. This is avoided by grouping similar stressors together within each training day, throughout the week.

Additionally, this can be used to isolate high- or low-velocity training in order to target the weaknesses within an athlete’s force-velocity profile. Using the example split above, Day 2 would play a more important role in the training of a force-deficient athlete while Day 1 would be more effective for velocity-deficient athletes. We are still training both ends of the spectrum within a week but manipulate the training volume, and therefore emphasizing certain aspects of the training stimuli, to fit the needs of the athlete’s physical profile.

WITHIN-SESSION PROGRAMMING

When training multiple physical qualities within a workout, it is important to perform exercises in an order that optimizes training adaptations and reduces the detrimental effects of neuromuscular fatigue. An effective training session will always start with a comprehensive warm-up routine, raising overall body temperature, warming up the muscles and joints, as well as “waking up” the nervous system so the athlete is ready for the work ahead. After that, we need a set of principles to guide how we will structure our training order.

principle of fatigability

Simply put, exercises that require higher neuromuscular output and physical readiness are more susceptible to performance detriments due to fatigue. These exercises are better performed at the beginning of a training session (after warm-ups) when the athlete is fresh and has all of their physical and mental resources. Max effort, max intent modalities like intensive plyometrics, high effort compound lifts and ballistics all fall under this category.

Contrastingly, exercises that require a lesser degree of neuromuscular output like accessory lifts, isolation lifts and stability training can be trained at the end of a session with little to no detrimental effects on training adaptations. If we use this principle to guide exercise order, this is what a typical concurrent power and strength training session might look like:

The same principle can be used if we were train both martial arts and S&C within the same day. Because of the importance of skills training, I would schedule it first. Pre-fatigue can be a tool to improve skill retention and transfer, but in most cases, only hampers skill acquisition and development by making it harder for combat athletes to participate in high quality, deliberate training.

PRIORITY

Prioritization is an exception to the principle of fatigability. An athlete should first perform exercises that are most important to their primary training goal (if they one that is clear-cut). Going back to our athlete is differing athletic profiles, a force-deficient athlete should focus on high-force producing exercises first thing in each training session in order to reap in the most training benefits. Likewise, a velocity-deficient athlete should perform high-velocity exercises before slower movements (the outcome is in line with the principle of fatigability but for different reasons).

Post-activation potentiation and contrast training

Post-activation-potentiation (PAP) is a phenomenon where rate of force development (RFD)/power is increased due to previous near-maximum neuromuscular excitations. This is another exception to the principles of priority and fatigability, whereby the athlete will deliberately perform heavy compound lifts first even if RFD/power is the primary goal.

I’ve written an article about this topic of within-session planning, covering these principles more in-depth. If you’d like to learn more, read “Exercise Order - Principles For Sequencing A Training Session”.

WRAPPING IT UP

Whenever I create an S&C program for combat sport athletes, I’m always considering all 4 layers of programming. Some of the specific methods I use like type of training-split or the type of volume/intensity undulating I use will change based on the athlete I’m working with, however, most of the governing philosophies (on the macrocyclic level - see Part 1) stay more or less the same.

It’s important for S&C coaches to adapt to information given in front of us, not be limited by scientific dogma, but at the same time, be willing to change and improve our philosophies over time. Since combat sports is a growing industry, so is S&C for combat sports. We must navigate through performance training with nuance.

The learning doesn’t stop there. Here are some combat sports S&C articles that will help you along the way.

Combat Sports Strength and Conditioning : Macrocycle & Mesocycle Planning [PART 1 of Programming Layers Series]

In this article, we’ll discuss several strategies and philosophies I use when preparing combat sport athletes, which layers they can be utilized in and how a better understanding of programming can help us more effectively coach high-performance combat sport athletes.

Given the complexities of combat sports performance, strength and conditioning programming must match the demands of the training environment by being adaptable and holistic. In order to achieve this, programming must consider all layers and timelines of training.

Programming and training periodization happens on 4 time scales (or layers) - Within session, on the microcyclic scale, mesocyclic scale and the macrocyclic scale. Each layer can be considered the lenses of which the S&C coach views training and physical preparation and must be planned accordingly.

In this article, we’ll discuss several strategies and philosophies I use when preparing combat sport athletes, which layers they can be utilized in and how a better understanding of programming can help us more effectively coach high performance combat sport athletes.

Some of the concepts I talk about will be familiar to those who have read my eBook “The Strength & Conditioning Handbook for Combat Sports”, while others maybe new to some of you.

This programming article series will be split into 2 parts.

In part 1 (this article), we will start with a low resolution view of training, in other words, the bigger picture. We will cover big concepts that guide our decisions when it comes to long-term athletic development and month to month training.

In part 2, we will work our way down to the specifics like week to week and day to day programming (higher resolution view).

READ PART 2 ON MICROCYCLE AND WITHIN-SESSION PLANNING PROGRAMMING HERE

the MAcrocyclic layer

In training periodization, the macrocycle is the largest division of training periods, usually several months in length or even a years. When planning on the macrocyclic layer in combat sports, we are concerned with the long-term development of athletes. What the overall career trajectory looks like (considering factors like training and competition age) as well as overall athletic development/progression from fight to fight.

Below are some philosophies and frameworks I use to govern development on the macrocyclic level.

LTAD Model

The long-term athletic development model (LTAD) model is a framework created by Dr. Istvan Balyi to guide the participation, training and competitive aspects of sports and physical activity throughout different stages of development for any athlete.

No matter what stage an athlete comes into the sport, a base must be built for performance potential to flourish in the future. Whether your athletes’ goal is to compete in boxing, wrestling or Judo in the Olympics, or turn to a career in prize fighting for international organizations such as the UFC or One Championship, a coach must see S&C as a long-term investment. Coaches that partake in short-term thinking - disregarding joint health, brain health and overall athletic longevity do nothing but limit the potential of an athlete.

Skill Practice Rules All

The skill practice rules all paradigm acknowledges that skill is the most important aspect of combat sports, rather than physical ability. S&C coaches new to the combat sports world are hesitant on adopting this philosophy (the ones who do fail to manifest this in their programming) as many of them view high performance training through a purely physical and bioenergetic point of view - thinking that maximum strength, power and great endurance (as objectified through lab testing numbers) is what ultimately influences the outcome of a fight.

However, by undervaluing sport-specific skills such as pattern recognition, tactical strategies and fight experience, these coaches make mistakes in the training process that sacrifices skill development and expression for superficial strength and power gains.

Without getting into too much detail, I’ve used this skill practice rules all paradigm to influence my programming so that training stress is distributed more optimally throughout training camps and S&C plays a supplementary role, allowing skill expression to shine on the night of a fight.

If you’d like to learn exactly how I apply this into my S&C programs, I highly recommend you check out the eBook I mentioned earlier.

The Barbell Strategy

Originally a financial investment strategy, the barbell strategy adapted to S&C involves utilizing “low-risk” training methodologies as the main driver behind performance improvements; only prescribing special developmental exercises and “high-risk” exercises when the foundational bases have been thoroughly covered.

With the rise of social media and wild exercise variations promising transfer to the sport, it’s easy to get lost and major in the minors. Landmine punches and brutal conditioning circuits have a place in combat sports S&C but plays a very small role in driving meaningful improvements in fighters.

As a rule of thumb, 80-90% of time should be invested in “low-risk” exercises, and the rest 10-20% into more specialized training. However, don’t fall into the trap of thinking “low-risk” exercises are don’t drive any improvements in sports performance or that they are picked blindly, they should still be selected with the physical demands of the specific sport in mind. A comprehensive needs-analysis of the sport needs to be performed beforehand. Given the limited time I may have with a fighter (2-3 sessions a week), I must select exercises that have a favourable cost-to-benefit ratio.

Looking at the bigger picture, the barbell strategy keeps my programming and exercise selection process grounded by reminding me what improvements I can realistically make with combat fights as an S&C coach and what influence I have over the training process.

Agile Periodization

This is a term coined by S&C coach Mladen Jovanovic. As described by Mladen:

“Agile Periodization is a planning framework that relies on decision making in uncertainty, rather than ideology, physiological and biomechanical constructs, and industrial age mechanistic approach to planning” (Jovanovic, 2018).

Agile periodization represents a training philosophy that’s based on the uncertainty of human performance and one that permeates multiple layers of my programming and planning.

Rigid periodization models that we S&C coaches learn from textbooks and university classes unfortunately have little success given the unpredictability of the real-world and the volatility of combat sports training schedules, competition dates and career trajectories. Furthermore, mindlessly following scientific dogma and abstractions give us a false sense of predictability and stability in the training/planning process.

While we still need to set objective long-term goals and have a vision of what success looks like for our high-performance athletes, the agile periodization framework encourages simultaneous bottoms-up planning: what does the next best step look like given the athletic and environmental constraints in front of us? Does the long term goal change with the new information we’re receiving about the athlete and their progress?

The mesocyclic layer

Mesocyclic planning is concerned with how training variables change from month to month - most of these strategies have fancy names and are ones you normally hear when reading about training periodization.

The overarching goal with mesocyclic planning is to create a training program that bests develops the athletic qualities a combat athlete needs in order to excel at their sport. Whether these qualities should be trained simultaneously, sequentially or in a specific order is what makes one periodization model different than the other.

Let’s explore a few options.

Block Periodization

Commonly confused with programs that simply have “blocks” or “phases” of training, block periodization (BP) is a specific periodization strategy popularized by soviet coaching figures like Verkoshanksy, Bondarchuk and Issurin (article here on a review on different types of training periodization). BP consists of distinct blocks of training aggressively targeting certain physical qualities, such as maximum strength, or plyometric ability (and doing the bare minimum to attempt to maintain other qualities). The basis behind BP is that elite-level athletes who are reaching the functional limits of their physical performance require highly concentrated training loads in order to further increase performance. This becomes problematic when translating it to the world of combat sports training. Here’s why:

Imagine a 4-week block dedicated to increasing maximum strength where the majority of your weight room training volume comes from heavy lifts above >85% of 1RM. The lack of a high-velocity stimulus combined with the fatigue incurred throughout this block will unquestionably hinder an athlete’s ability to develop new skills on the mats or clock in high-quality sparring sessions.

The physical demands of combat sports are not extreme (compared to pure-strength or pure-endurance sports), what’s important is improving key qualities slowly over time while still maintaining physical and mental energy to excel in the practice room - where it counts.

It’s a good idea to separate training into distinct blocks/phases with clear goals, However, implementation of BP, characterized by aggressive investments into single traits and heavily reliance on cumulative and residual training effects, is best left for sports like cycling and powerlifting.

Triphasic Training

Triphasic training, popularized by Cal Dietz, also shares some elements of block periodization, where each block heavily emphasizes the eccentric, isometric and concentric (3 phases - triphasic) muscle actions sequentially to improve speed and power at the end of the block.

Typically, a general preparation phase (GPP) is done prior to jumping into a 6-week triphasic training phase consisting of 2 weeks of eccentric focus, 2 weeks of isometric focus and 2 weeks of concentric focus. This is all capped off with a high velocity peaking/realization block lasting several weeks (depends on the athlete/sport/schedule).

Much like block periodization, triphasic training requires adequate preparation time before a fight or competition and can run into the same problems that BP does, of sacrificing quality of skills training in order to further build physical abilities.

Some coaches have made this work, notably William Wayland of Powering Through Performance, who adapted the triphasic model to MMA athletes, compressing the model and by utilizing supramaximal loading. William breaks it down much better than me so I suggest reading up on it here: “Applying The Compressed Triphasic Model with MMA Fighters”.

Concurrent Method

Like the name suggests, this method involves developing multiple physical qualities concurrently, from month to month. The emphasis on each quality is not implemented as aggressively as it would be in BP or a triphasic set up, so it allows for more programming flexibility - changing intensities and volumes where the S&C coach sees fit (see agile periodization).

By training concurrently, the training stimulus is spread amongst all physical qualities (endurance, strength, plyometric ability, power-endurance, etc) - no physical trait is being neglected, therefore an athlete’s physical readiness remains relatively stable from month to month. A potential downside to this method is that if we’re spreading the training volume thin amongst different traits, we risk watering down the training process and end up not making any tangible process in each area.

Contrastingly, this coincides with the concept of minimal-viable program (MVP) brought up by Mladen Jovanovic, a concept that states that a program that covers all areas will, over time, tell us what changes need to be made based on strengths, weaknesses and any data that comes out of that. Each subsequent training phase will then be modified to suit the needs of the athlete.

These paradigms and philosophies that occur on the macro- and mesocyclic level govern the way we view physical preparation for combat sport athletes, also affecting the decisions we make downstream. In part 2, we will go over strategies we can apply on the microcyclic level and within any given S&C session. (Click here to read part 2).

Alternatives to Olympic Weightlifting For Power Development

Olympic weightlifting movements in the S&C environment is a controversial topic because some coaches are quite dogmatic about it’s use in power development. There are pros and cons to using them, depending on the context. Coach Jason lays out reasons to use alternatives and in what situations they would be best utilized.

This is a guest post written by Vancouver-based personal trainer and S&C coach Jason Lau of Performance Purpose. Olympic weightlifting movements in the S&C environment is a controversial topic because some coaches are quite dogmatic about it’s use in power development. There are pros and cons to using them, depending on the context. Coach Jason lays out reasons to use alternatives and in what situations they would be best utilized.

Olympic Weightlifting for S&C

Olympic Weightlifting is a sport in which athletes attempt to lift a maximum weight overhead using the two competition lifts: Snatch and Clean & Jerk. These competition lifts and their derivatives: hang snatch/clean, push press, snatch/clean pulls, power clean/snatch/jerk, can often be seen programmed outside of the sport, in an athlete’s strength and conditioning program.

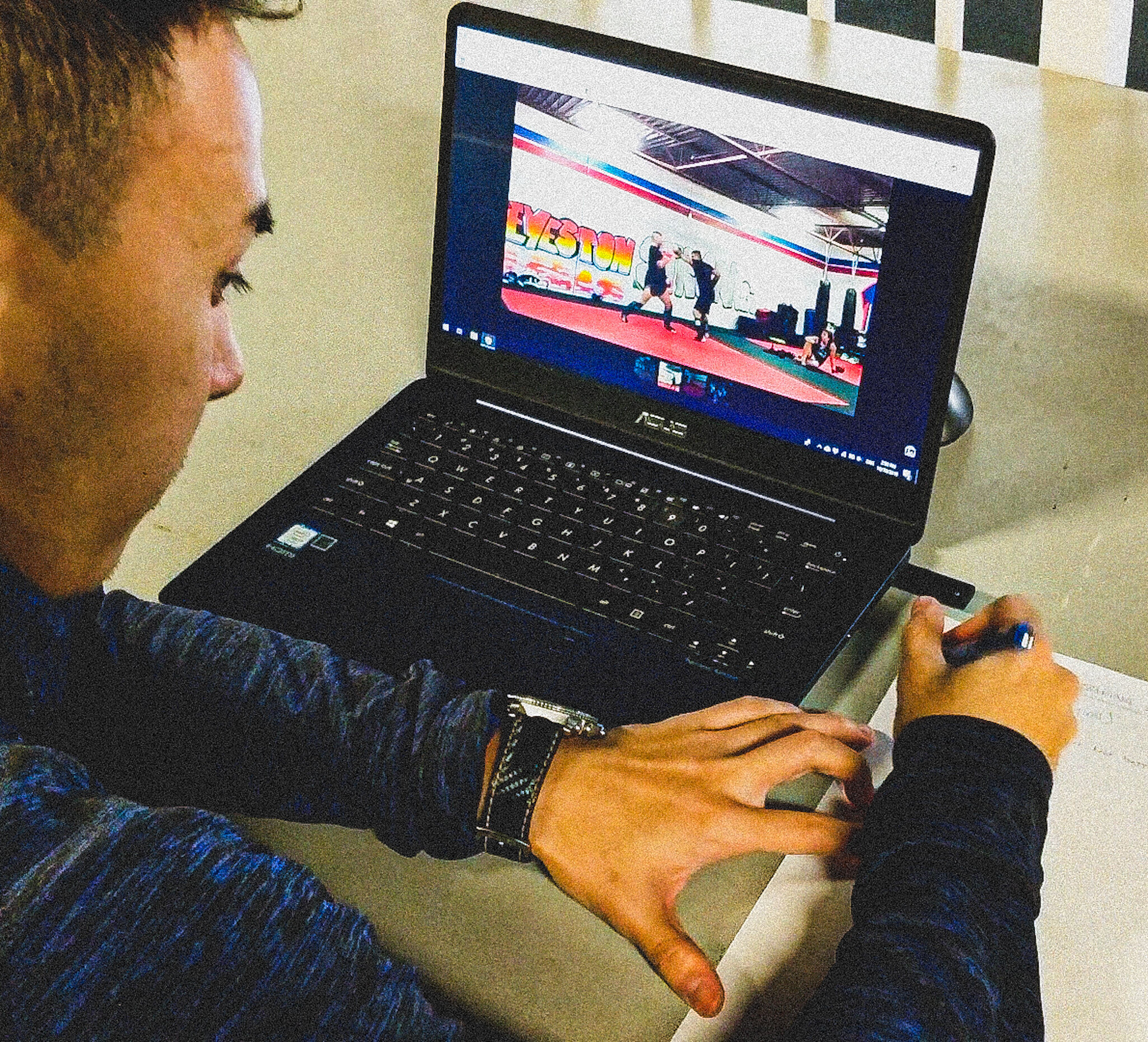

Due to the identical triple extension movement pattern (extension of ankles, knees and hips), seen commonly in weightlifting and sports, an athlete training the weightlifting movements can greatly improve the transfer of power from feet through torso to hands, as well as athletic coordination. In that sense, weightlifting can serve as a specific preparatory exercise that matches the high force and high velocity seen in sport that traditional heavy lifting cannot satisfy.

To quote Cal Dietz – “In order for an athlete to become fast, they must train fast.”

Then Why Use Alternatives?

Despite the power development that the weightlifting movements provides for athletes, there are also risks that you will have to consider as well.

Aside from aggravated joints such as knees, shoulders and hips, the lifts requires a high technical demand to perform correctly and safely. Time is required to master the technical aspect of the lifts. Time that should not be carelessly managed when an athlete is training for an upcoming game or season. Another factor to consider is the amount of training experience the athlete has in the weight-room. Mobility and injury restrictions may also interfere with the athlete’s ability in performing the lifts. Lack of ankle and overhead mobility and stability are restrictions are common and should be addressed before progressively overloading as it may lead to injury down the road.

Power development is also specific. In the world of S&C, specificity is king as game/competition date draws close. Does the athlete have to move heavy external or light loads within the sport? This will determine what type of loading scheme and stimulus is required. For example, a football linebacker will lean towards higher intensity hang cleans including prioritisation of strength due to the demands of their sport. On the other hand, the intensities a volleyball athlete’s program would see lighter intensities as external load is not needed to the same degree within the sport.

By taking into consideration of the limitations listed previously, alternatives can be performed and taught with relative ease while mimicking the classic lifts in velocity and movement pattern. Through alternatives, we can achieve the same stimulus that weightlifting movements bring while still improving strength in high-velocities.

Alternative Exercises

Trap Bar Jumps – Trap Bar Jumps is one of the go-to replacements for weightlifting. A previous study done by Timothy J. Suchomel indicates that when utilizing lighter loads (<40% of 1RM), the jumps displayed higher force output compared to a hang power clean at the same load. The learning curve of this exercise is relatively low where the majority of athletes can perform without difficulty while staying true to the natural movement pattern of jumping. With the versatility of the trap bar jump, it can be performed with a counter-movement while loaded with bands or weights.

Squat Jumps – Squat Jumps is a great transition towards power as an athlete is transferring out of their strength focused block. Aside from a smooth transition, a squat jump replicates the second pull during a clean. This can be performed from a quarter squat depth or full squat depth, all dependent on the athlete’s goals. Considering this exercise utilizes the squat movement pattern, it is different from an athlete’s natural jumping form so it may not satisfy the need of specificity.

Medicine Ball Toss – The med ball toss is a great exercise to have within one’s arsenal. Ballistics are predominantly concentric in nature allowing the athlete to focus on the acceleration phase without having to catch or decelerate at the end. The ability to reap the benefits of fast twitch muscle fibre contractions without the negative effects of eccentric forces can benefit the athlete. Tosses can be expressed throughout multiple planes of motion as well, not only vertically, that is what makes this movement so versatile.

Prowler Push – The vast majority of alternatives are bilateral in nature, but with Prowler Pushes and drags, we can achieve unilateral power with little technical demand on the athlete. This allows the athlete to drive off the ground and transfer force through the torso and into the prowler with no eccentric forces. This movement is versatile and can serve as a special developmental exercise for athletes in frequent sprinting sports.

To weightlift or not to weightlift?

That is the question. My answer? It depends.

I encourage coaches to look at the bigger picture. Does the athlete have enough time to learn the technicalities of the lifts? Are the athlete’s movement patterns proficient enough? Does the athlete have enough weight-room experience? Are there any severe mobility or stability issues that the athlete has to address beforehand? Are the alternatives sufficient for the time being? There is more than one route to achieve ideal athletic qualities. The factors that set apart good and bad S&C programs from each others are the risk to reward ratio, efficiency and specificity.

References

Suchomel, T. J., & Sole, C. J. (2017, September 1). Power-Time Curve Comparison between Weightlifting Derivatives. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5592293/

Shattock, K. (2018, February). The Use of Olympic Lifts and Their Derivatives to Enhance Athletic / Sporting Performance: A Mental Model. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322901416_The_Use_of_Olympic_Lifts_and_Their_Derivatives_to_Enhance_Athletic_Sporting_Performance_A_Mental_Model

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

JASON LAU is a Strength & Conditioning / Physical Preparation coach and owner of PERFORMANCE PURPOSE based out of Richmond, BC. His passions include coaching and refining badminton, volleyball and hockey athletes, beginner to provincial level powerlifters, return-to-play rehab and general population clientele of all ages.

He aims to offer a systematic and evidence based approach to off-season and in-season training, translating the athlete’s weight room progress towards their specialized sport. His goal is to drive improvement and progress of each individual within the field of athletic performance.

Website: https://performancepurpose.ca/

Instagram: @performancepurpose

Concurrent Training: Science and Practical Application

Concurrent Training is the combination of resistance and endurance training in a periodized program to maximize all aspects of physical performance. This article will review the science behind concurrent training and help you get the most out of your training sessions.

Concurrent Training (CT) is defined as the combination of resistance and endurance training in a periodized program to maximize all aspects of physical performance. Unless an athlete is in a pure-power sport like Olympic Weightlifting, or a pure-endurance sport like long distance cycling; a combination of both power-related and endurance-related attributes are required to excel in mixed-type sports. Mixed type sports are sports that depend on several different energy systems and different strength and speed properties. MMA, boxing, basketball, soccer, hockey and many other team-based sports fall under this category.

In the world of bodybuilding and strength sports, cardio is used as an umbrella term for all types of endurance training protocols. Often as a joke among lifting circles, cardio has been stigmatized to "steal your gains", so far to the point that some lifters see it as a badge of honor to be out of shape and possess almost no cardiovascular conditioning in return for being able to lift a massive amount of weights.

In the world of endurance sports like running and cycling, strength training can be seen as an unnecessary training method that adds unwanted muscle mass to the frame of an endurance athlete, possibly slowing them down and being detrimental to their performance. The term "meathead" might even be applied to people who lift weights.

This article will shed some light on what cardio and strength training has to offer to each training demographic/niche and how a mixed-typed athlete can best organize their training so they reap in the benefits of both training modalities with little to no interference.

The Science and theories behind ct

In one of the first research studies carried out on the effects of concurrent training, Hickson (1980) observed that training both strength and endurance qualities simultaneously had detrimental effects on strength development but did not negatively impact aerobic qualities. Building off of research by Hickson, more recent studies have shown a wide variation of responses in concurrent training, both positive and negative. This suggest that CT methods are still inconslusive and variables such as genetic differences, modality of endurance training, nutritional status and training time may play a role in mediating the effects.

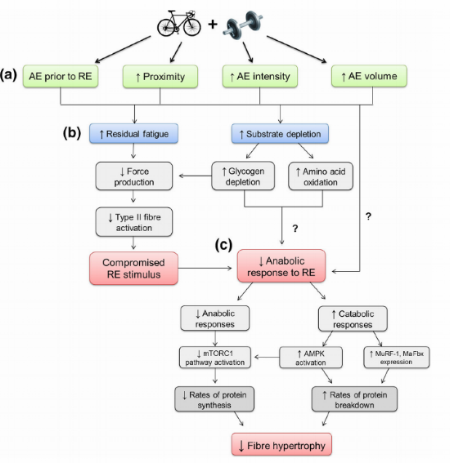

Termed the molecular signaling theory, it has been hypothesized that the distinct molecular signaling pathways of strength and endurance exercise adaptation may be incompatible and inhibit the development of each other.

Other theories speculate that the poor management of both resistance and endurance exercise variables may expose athletes to higher incidents of overreaching and overtraining. For example, the high volume nature of endurance training paired with heavy strength training may make recovery more difficult, increasing the risk of overtraining and injury to an athlete. In conjunction with observing the effects of CT, uncovering the potential mechanisms behind the molecular signaling theory is needed to understand how strength, power and endurance can be developed simultaenously.

Molecular signaling theory

Resistance training adaptations such as muscle fibre hypertrophy, strength and power acquisition are known to be mediated by molecular signaling pathways known as the AKT and mTOR pathways. Resistance exercise that create large force outputs, mechanical tension and stretch, as well as muscle damage and swelling are activators of these hypertrophic pathways (Brad Schoenfeld talks more in depth about this in his frequently cited research article - "The Mechanisms of Muscle Hypertrophy and Their Application to Resistance Training"). Many of the compound powerlifts that recruit larger amounts of muscle mass have the capability to create large force outputs and mechanical tension, while exercises such as isolation exercises taken to failure, drop sets, supersets, giant sets, contribute more to metabolic stress and cell swelling.

In contrast, prolonged and repetitive low intensity muscle contractions activate signaling pathways involving the enzymes AMPK and CaMK, which are responsible for adaptations related to endurance training such as mitochondrial biogensis; allowing you to walk, run, swim and bike further and more efficiently.

Capturing the attention of researchers, the observed suppression of mTOR signalling pathways by increased AMPK activation has been the focus and basis behind the molecular signaling interference theory. AMPK activation downregulates and can blunt the hypertrophic response to a resistance training workout or program by inhibiting mTOR and can increase protein degradation through other pathways we won't get too deep into. mTOR can even be downregulated indepedent of AMPK activation, through a family of proteins called SIRT (more information here for the nerds). What you need to know is that when performing cardio training during a resistance program, muscle hypertrophy, strength and power can be compromised.

So were the bros right all along? Does cardio in-fact, kill your gains?

Not so fast. It is not uncommon to see increased endurance performance or improved resistance training outcomes with CT, thus several studies have made arguments for the limitations of the interference theory. In some cases, resistance training can upregulate AMPK, and aerobic exercise can also induce increases in mTOR activity; therefore a positive transfer effect might be present when intensity, volume and frequency of each training modality are strategically manipulated.

It should also be noted that the results of research studying the acute effects of exercise and molecular signaling cannot always be predictive of future chronic adaptations. If athletes have no CT experience, the interference effect might be just occur until the athletes acclimatizes the the CT methods. It is also possible that the interference effect may not be present until later into a training cycle where there is an accumulation of resistance and endurance training fatigue due to increased training loads, or intensity. For example, the original CT study by Hickson (1980) found there were no interference effects until the 8th week of training.

Since molecular signalling has been found to be highly variable depending on the training status of the individual (strength trained vs. endurance trained vs. completely untrained), CT variables must be prescribed based on athletes' current training status and previous training experience.

Concurrent Training Effects on Resistance Training Adaptations

Varying modality, intensity, frequency and volume of training has been shown to affect the magnitude of molecular signaling and protein synthesis. Therefore we know that the degree of interference between signaling pathways can also vary depending on programming variables. Since AMPK downreulgates mTOR signaling and NOT vice versa, its hypothesized CT can be more detrimental to resistance training (RT) related adaptations compared to endurance training (ET) related adaptations.

Muscle Hypertrophy

Muscle size and hypertrophy is a highly sought after adaptation in the fitness world, both as a means to improve metabolic health, and a way to achieve an aesthetic physique.

With several studies concluding that CT blunts muscle hypertrophy, excessive training volume has been predicted to be the cause of overtraining and fatigue when comparing CT groups to resistance training only groups. Based on our knowledge of exercise adaptations, we should know that RT volumes performed by an elite bodybuilder cannot be concurrently trained successfully with ET volumes performed by an elite triathlete due to nutritional and time constraints. However, to date, there is no conclusive evidence that hypertrophy is blunted when low-volume aerobic exercises is added into a training program; some studies have even shown it might mitigate muscle loss (Study #1, Study #2). High volume ET on the contrary, can be detrimental due to the factors discussed above (interference theory OR overtraining/fatigue theory OR... both). For practical recommendations on how to avoid interfering with your hypertrophic workouts, read below in the practical application section.

Strength & power

In a large scale meta-analyses of CT effect sizes, Wilson et al (2012) observed that in many studies, power was significantly lowered during CT while muscle cross sectional area and strength was maintained. This suggests that force at high velocities (think of a vertical jump, NOT a heavy squat) may be affected to a more significant degree with concurrent ET than force at lower velocities. The mechanism behind this could be attributed to motor unit and specific muscle fiber type innervation. During classical long duration endurance exercises, the majority of muscle action and force production comes from low threshold, fatigue-resistant type I muscle fibers. There may be a shift from type IIx fibers to type IIa fibers or type IIa to type I fibers to accommodate the oxygen-demanding adaptations of endurance exercise during concurrent training therefore aerobic exercise can be detrimental to athletes that require a high rate of force development rate and power when poorly programmed into a periodized plan.

To better compliment the demands of strength and power sports, prescribing lower volume - higher intensity and velocity interval type ET may be more beneficial in terms of maintenance and improvement of power. This may be because of the similarities in the motor unit/muscle fibre recruitment patterns in RT and high-intensity based ET. When viewing this from an interference theory stand point, the high energy costs and high activation of AMPK from high-intensity ET could potentially magnify the interference effect but the research does not support this claim as there has been no cases of muscle mass loss when high-intensity ET is prescribed in a low-volume fashion. Research isn't conclusive but it is clear the intensity and volume of endurance training affect muscular strength and power outcomes.

When it comes to training modality, it is hypothesized that modalities that require a lot of eccentric muscle action can cause excessive muscle damage, further impeding the muscle recovery process from a challenging RT session. Because of this, predominantly concentric movements, are favored over running (a movement that includes a lot of eccentric contractions - think of every time your foot strikes the ground), like cycling and prowler pushes. Cycling, specifically hill climbing, can also resemble resistance-like loading patterns and can induce lower body hypertrophy that may compliment RT adaptations. Following this stream of thought, other ET modalities that possess lower eccentric muscle action and lower impact stress like swimming or modalities that have similar loading patterns to resistance training such as prowler-pushes and sled drags can also be used to improve cardiovascular conditioning when training concurrently.

Concurrent Training Effects on Endurance Adaptations

Well-trained athletes often show different responses to exercise compared to untrained individuals, endurance athletes are no different as they may see dissimilar improvements from RT compared to untrained or already resistance-trained individuals. High volume and high frequency endurance training make it hard for endurance athletes to improve muscle size, strength and power without cutting into the recovery process of ET. Paired with the high energy expenditure and AMPK levels from ET, CT can be problematic for endurance based athletes.

Wang et al (2012) showed that resistance training following endurance training elicited greater PGC-1a actavation (a regulator of energy metabolism and endurance adaptations) and therefore more oxidation capacity improvements than endurance training alone. The increase in activation of PCG-1a was thought to be related to the high amount of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and lactate concentrations produced during CT vs. endurance training alone. AMPK activation however, was not a plausible explanation for the improvements in oxidative capacity as AMPK was similar in both the CT and ET-only group. The researchers suggest that the RT portion of the CT group upregulated mTOR, which had a positive effect on PGC-1a. The interactions between mTOR and PGC-1a also have implications for muscle and endurance performance.

Another study concluded that resistance training has positive implications for endurance performance, mainly due to increases in type IIa muscle fibers and a greater potential for force production (Study). This means endurance athletes that concurrently resistance train can improve their average and peak power outputs, which play a big factor during races and time trials. In addition, a study looking at the effects of CT found that pairing strength circuit training along with an ET program (same workout session) improved aerobic performance more than an ET program alone where VO2max and 4km time trial performance both increased slightly more in the CT group compared to the ET only group. The beneficial effects of RT for endurance athletes cannot be overlooked!

Resistance training can also benefit endurance events of different durations. For shorter, more anaerobic dominant endurance events like the 400m/800m run, most swimming events and many team sports, performance can be improved by increasing muscular strength and neuromuscular function that can't be achieved with ET alone. For long aerobic endurance events and competitions like marathon runners, and triathletes, improvements in performance can be attributed to the higher economy of movement induced by RT (study), which simply means endurance athletes that resistance trained were able to more efficiently use their energy to travel at any given velocity, saving them energy in a long race.

Concurrent Training Timing

(AE = Aerobic Exercise)

(RE = Resistance Exercise)

Disclaimer: This is not my chart.

If we base our training order off the molecular signaling theory of the interference effect, ET would be best performed prior to RT (within the same day). Since AMPK downregulates mTOR and not vice versa, an ET session that raises AMPK levels will not have a chance to interrupt mTOR signalling if RT is performed after. But we also need to take into account other facts to help us maximize training adaptations and minimize any interference.

The interference theory can manifest in the form of negative interactions between protein activity and molecular signalling, but coaches cannot overlook the more simple explanations as to why there might be an interference effect when training several physical attributes or modalities. Reduced training quality can also be an explanation as to why CT causes interference problems. For example, after performing a ET session, performance in the subsequent RT session may be diminished due to pre-exhaustion. This is problematic if a particular athlete needs to prioritize his/her RT session because of their personal goals, weaknesses or position on a sports team. Coaches and athletes must plan and prioritize which training sessions are more important and the introduction of rest and nutrition must be taken into account to mitigate any interference effects.

In order to minimize the fatigue and the interference effect, a 24-hour recovery period between training sessions is suggested; the longer the better. However, this suggestion is often not practical for subelite or elite athletes that want to or are required to train 2 and up to 3 times a day. Based on the time course of AMPK elevation and it's downregulation of mTOR signaling, a minimum recovery time of 3 hours is suggested between ET and RT sessions. Although 3 hours is enough to reduce the molecular signaling part of the interference theory, its also suggested that 6 hours or more is needed to reduce the muscular fatigue from the previous ET bout and retain muscular performance during a subsequent RT session. When high-intensity ET was performed prior to RT, force production was reduced for at least 6 hours, while the capacity to perform higher volume RT was also diminished for up to 8 hours. As noted by Robinuea et al (2014), technical and tactical training sessions in team sports also have an cardiovascular and endurance component to it, not scheduling adequate rest before a subsequent RT session could be detrimental to performance.

Nutritional Protocols For Concurrent Training

Scheduling adequate recovery time in between RT and ET sessions can also allow for nutritional interventions to decrease the interference effect. Since AMPK is increased when the energy status of an athlete is low, RT in theory, is better performed in a fed-state to allow for optimal mTOR signaling post-workout. Ingesting carbohydrates and high-quality, leucine-containing protein supplements or whole foods to fuel post-exercise-induced increases in muscle glycogen and protein synthesis is crucial when training concurrently. In contrast, performing ET while in a fasted state (low-intensities) can promote PGC-1a and AMPK signaling, exemplifying ET adaptations.

Here is my article on nutritional periodization.

Here is a research review on nutritional methods used to maximize concurrent training.

Practical Application & Recommendations

In light of this research, endurance athletes should focus on programming moderate volume, moderate to high intensity RT around their prioritized ET, sport-specific, sessions.

Strength and power-based athletes should include low to moderate volume ET in order to attenuate the interference effect while still reaping in the benefits of ET such as improving blood flow for recovery or building some general work capacity in the off-season or restoration period.

For mixed-type and team sport athletes, the proportion of RT and ET should be strategically programmed based on the energetic and muscular demands of the sport, an athlete's strength & weaknesses, as well as their position on the team.

The Dilemma

So when it comes to within-day training order, there is a dilemma on whether RT should come before or after ET.

If RT comes before ET, performance during the RT session will hypothetically be higher quality due an absence of residual ET fatigue but hypertrophic signaling will be downregulated after the ET session.

If RT comes after ET, the glucose/substrate depletion and residual fatigue from ET will reduce the training quality of the RT session and may also blunt the hypertrophic response. Specifically, AMPK is upregulated by increased energy expenditure and substrate depletion, negatively affecting the mTOR pathway.

So what do you do? It really depends on your goals.

For me to offer any rigid periodization schemes or training methods would be counterproductive. Coaches and trainers need to plan their athletes' demands, circumstances, strength, weaknesses and limitations. Training should be evidence-based but there is also a lot of room to be creative in their program design. I'll give you some tips:

If You Are training for hypertrophy...

Endurance training after resistance training if your ET session is low to moderate volume. The ET session ideally will use different muscles than the ones emphasized in your RT session. It is still unknown whether the molecular signaling theory of the interference effect is peripherally driven - meaning muscle specific, or if it is systemic (whole body interference regardless of muscle trained) sessions. If the interference effect is peripherally driven, a viable strategy would be to perform an upper body lifting session, followed by a lower body only cardio session like cycling.

Endurance training before resistance training if you have 3-6 hours of recovery time in between the two sessions and are able to refuel with carbohydrates and some protein.

Use low-impact ET modalities like prowler, cycling, sled drags, elliptical, swimming, etc... to avoid any more stress on your joints and muscles

Use moderate-volume, low-intensity ET to improve heart health, blood flow to working muscles as a form of recovery, control energy expenditure to mediate diet/macros and calories intake.

Use Zone 1 to warm up prior to lifting sessions.

Use Zone 2 on off days or as a separate training session to improve the benefits discussed above (heart health, energy expenditure, etc.)

Additionally, you can use Zones 4 and 5 as a "finisher" to hypertrophy-based workouts as a form of metabolic stress. These zones recruits similar muscle fibers and uses the same energy systems as strength training sessions.

If you are training for strength...

Endurance training after resistance training if your ET session is low to moderate volume. The ET session ideally will use different muscles than the ones emphasized in your RT session. Same rule applies from the hypertrophy section.

Endurance training before resistance training if you have 6+ hours of recovery time in between the 2 sessions and are able to refuel with carbohydrates and some protein. Since strength training emphasizes sport technique (powerlifting, weightlifting, Strongman) more so than general hypertrophy training and operates at higher intensities (as a % of 1RM), it is extra important that muscle residual fatigue is as low as possible.

Use low-impact ET modalities like prowler, cycling, sled drags, elliptical, swimming, etc... to avoid any more stress on your joints and muscles.

Use Zone 2 on off days or as a separate training session to improve the benefits discussed above (heart health, energy expenditure, etc.) I personally like doing Zone 2 easier, low-impact aerobic workouts with a mobility and stretching routine to promote recovery on off days.

Zone 4 and 5 can be used as intervals on the prowler, sled, rower or ski-erg to increase top end cardiovascular conditioning to help you improve your work capacity for high volume lifting workouts.

If you are training for power...

Endurance training session after your resistance training session if your ET session is low to moderate volume.

Endurance training before resistance training is definitely not recommended. If it must be done, take as much recovery time as possible between sessions and refuel adequately and avoid working the same muscle groups. Pre-fatigued power workouts can be dangerous! Ideally rest 24+ hours.

Use low-impact ET modalities like prowler, cycling, sled drags, elliptical, swimming, etc... to avoid any more stress on your joints and muscles

Use Zone 2 on off days or as a separate training session to improve the benefits discussed above (heart health, energy expenditure, etc.) I personally like doing Zone 2 easier, low-impact aerobic workouts with a mobility and stretching routine to promote recovery on off days.

If you are an long event endurance athlete...

In almost all situations, resistance training AFTER endurance training is the best choice. You avoid pre-fatiguing yourself before your sport-specific training sessions (endurance training) and avoid downregulating mTOR to any significant degree.

Resistance training should focus on complex and compound exercises that span across several different muscles and movement types. Use weights anywhere from 70-90% of your 1RM. This is important for building a strong and healthy body that can withstand the high volumes of endurance training by building tissue resilience, tendon strength and core strength. Avoid using silly training methods like 30+ rep sets with 50% of your 1RM in hopes of building muscular endurance. Endurance will be built specifically in your sport already.

Time is valuable. Don't fall into the trap of training on unstable training surfaces or overly-specific exercises that try to mimic movements from your endurance sport. Stick with the basics. Push, pull, hip hinge, squats, etc...

Endurance athletes training in the off-season or restoration period can experiment with fasted training. More on this in my nutritional periodization article.

If you are a shorter event endurance athlete...

In almost all situations, resistance training AFTER endurance training is the best choice. You avoid pre-fatiguing yourself before your sport-specific training sessions (endurance training) and avoid downregulating mTOR to any significant degree.

Shorter event endurance athletes like 400-800m runners or track cyclists will greatly benefit from resistance training and is almost a requirement to excel in many short endurance sports. Use weights anywhere from 70-100% of your 1RM to build muscle mass and strength. Power training can be included using anywhere from 30-70% of 1RM to match the demands of the sport and can benefit endurance athletes involved in sports that require bursts of high-intensity efforts.

Again, don't fall into the trap of training on unstable surfaces or overly-specific exercises. Exercise selection though, should be more carefully planned to match some of the movement patterns seen in the endurance sport. There is a bigger carry over for shorter event endurance athletes vs. longer event athletes.

Endurance athletes training in the off-season or restoration period can experiment with fasted training. More on this in my nutritional periodization article.

If you are a mixed type athlete or team sport athlete

Mixed type sport athletes can have vastly different demands depending on the sport itself and the position played. Luckily through a needs-analysis, all sports can be plotted onto a endurance and strength attribute spectrum. Below is a figure outlining the physical demands of several sports.

Start by mapping out the specific strength and endurance demands, movement patterns, and energy demands of your position or sport and follow the principles discussed above to get the most out of your training sessions!

![Combat Sports Strength and Conditioning - Microcycle & Within-Session Programming [Part 2 of Programming Layers Series]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1605708338077-FWV40X4D3O675XD8QX5Q/Shared+from+Lightroom+mobile.jpg)

![Combat Sports Strength and Conditioning : Macrocycle & Mesocycle Planning [PART 1 of Programming Layers Series]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1605110722911-P7CE6O4VILYCVBEJ9R58/muay-thai-jump-rope.jpg)

![[Fight Camp Conditioning Guest Post] Bridging The Gap: Conditioning For Combat Sports](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1585917228624-NZJGW93SQK2P6F890J2A/New+article+title+pic.jpg)

![[Published on SimpliFaster.com] Individualizing and Optimizing Performance Training For Basketball](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1559464401554-UTSFUHZQUTNOISFNVX1P/Daryyl-Wong-Court.jpg)

![Tapering & Peaking: How To Design A Taper and Peak For Sports Performance [Part 2 of Peaking Series]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1501283047888-1OMY4OC27GHE81P94CPG/mountains-sport-nature-human-mountain-climbing-wallpaper-hd-black-1920x1080.jpg)

![Overreaching and Overtraining [Part 1 of Peaking Series]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1501052506104-FOT7NYG35KYOVLK3J12R/crossfit.jpg)