Combat Sports Strength and Conditioning - Microcycle & Within-Session Programming [Part 2 of Programming Layers Series]

In part 2 of this article series, we’ll discuss principles and training methodologies that can be used to optimize combat sports training within-session and within the week.

Given the complexities of combat sports performance, strength and conditioning programming must match the demands of the training environment by being adaptable and holistic. In order to achieve this, programming must consider all layers and timelines of training.

Programming and training periodization happens on 4 time scales (or layers) - Within session, on the microcyclic scale, mesocyclic scale and the macrocyclic scale. Each layer can be considered the lenses of which the S&C coach views training and physical preparation and must be planned accordingly.

In this article, we’ll discuss several strategies and philosophies I use when preparing combat sport athletes, which layers they can be utilized in and how a better understanding of programming can help us more effectively coach high performance combat sport athletes.

Some of the concepts I talk about will be familiar to those who have read my eBook “The Strength & Conditioning Handbook for Combat Sports”, while others maybe new to some of you.

In part 2 (this part), we will discuss the specifics week to week and day to day programming (higher resolution view).

Read PART 1 on Macrocyclic and Mesocyclic Training Here

the microcyclic layer

Programming on the microcyclic layer is concerned with optimizing training on the weekly level. Given the amount of sessions in a combat sports athletes’ schedule, we must consolidate them by avoiding any interference effects and create systems that can manage training stressors more consistently. Here are some guiding principles and strategies that you’ll find in my S&C programs.

High/low structure

I use a high/low structure to guide the initial parts of my program planning; a system popularized by track coach Charlie Francis to categorize running intensity and it’s affect on speed adaptations.

“High” training days consists of training modalities that require a large amount of neuromuscular-activation, a large energy expenditure and/or a high cognitive load - all stimuli that require a relatively longer period of full recovery (48-72 hours). Conversely, “low” training days are less neurally, bioenergetically and mentally demanding, requiring a relatively shorter period of full recovery (~24 hours).

Adapted to the world of combat sports, all training modalities, from sparring, technique work, heavy bag training to weight room sessions can all be categorized into high and low. This allows us to visualize the training and recovery demands of sessions throughout a full week of training.

Ideally, we would schedule training so that we alternate high and low training days so that the athlete is adequately rested for the most demanding sessions, but the reality of the fight game makes this challenging in practice. Some sessions, on paper, fall in between high and low categories in terms of physiological load. Regardless, using a high/low structure is a great start to help manage training stress within a week of training.

Condensed conjugate method

First of all, the conjugate method (CM), originally created for powerlifting performance by Louie Simmons of Westside Barbell uses Max Effort (close to 1RM lifting), Dynamic Effort (low % of 1RM performed in high-velocity fashion and Repetition Effort (moderate % of 1RM performed for ~8-15 reps) all within a training week. The CM is based on a concurrent system (I discussed this in part 1, where training aims to develop several physical qualities within a shorter time frame - week and month).

The first time hearing of the condensed conjugate method (CMM) was from Phil Daru, S&C coach to several elite combat sport athletes out in Florida, USA who adapted the CM method to fit the tighter training schedule of fighters.

What is originally a 4-day split (CM) is condensed into 2 days (CMM). This is what the general structure/training split looks like within a week.

Day 1:

Lower Body Dynamic Effort

Upper Body Max Effort

Repetition Effort Focusing On Weaknesses

Day 2:

Upper Body Dynamic Effort

Lower Body Max Effort

Repetition Effort Focusing On Weaknesses

Max effort and dynamic effort training are both performed on the same day, however, to mitigate neuromuscular fatigue, they are rotated based on upper body and lower body lifts. If upper body compound lifts like heavy presses and rows are performed that day (max effort), bounds and jumps will be trained for the lower body to avoid excessive overload.

Similar to most concurrent-based training splits, a large benefit comes from the fact that movements are trained within the whole spectrum of the force-velocity curve (see figure below). Max effort training improves the body’s ability to create maximum amounts of force - grinding strength, while dynamic effort trains the body to be able to produce force at a faster rate - explosive strength/strength. Repetition effort is then used to target weak points and to create structural adaptations like muscle hypertrophy and joint robustness.

The CMM also shares some of the drawbacks of concurrent-based training set-ups. Single athletic qualities progress slower since multiple are being developed at the same time, however, this is only a minor issue considering the mixed demands of many combat sports. Certain modifications can be made to the template or perhaps block periodization can be utilized (see Part 1 of the article) if working with athletes that are clearly force-deficient or velocity-deficient (see the next section on velocity-split). Nonetheless, a pragmatic way to organize both high-velocity and slow-velocity exercises within a training week. I’ve had success implementing this type of training split in my combat sports S&C programs.

Velocity-split

Sticking with the theme of a concurrent-based system within the training week, another way to set up a microcycle is using a velocity-split. For example, in a 2-day training split, high-velocity exercises and low-velocity exercises would be trained separately.

Day 1:

Upper Body Plyometrics & Ballistics

Lower Body Plyometrics & Ballistics

Speed-Strength Exercises (Loaded throws, Olympic Lift deratives, Kettlebell swings, etc)

Day 2:

Upper Body Max Strength Lifts

Lower Body Max Strength Lifts

Repetition Effort Training (70-85% of 1RM)

Isolation Exercises

With concurrent training, we risk pulling an athlete’s physiology in opposite directions. This is avoided by grouping similar stressors together within each training day, throughout the week.

Additionally, this can be used to isolate high- or low-velocity training in order to target the weaknesses within an athlete’s force-velocity profile. Using the example split above, Day 2 would play a more important role in the training of a force-deficient athlete while Day 1 would be more effective for velocity-deficient athletes. We are still training both ends of the spectrum within a week but manipulate the training volume, and therefore emphasizing certain aspects of the training stimuli, to fit the needs of the athlete’s physical profile.

WITHIN-SESSION PROGRAMMING

When training multiple physical qualities within a workout, it is important to perform exercises in an order that optimizes training adaptations and reduces the detrimental effects of neuromuscular fatigue. An effective training session will always start with a comprehensive warm-up routine, raising overall body temperature, warming up the muscles and joints, as well as “waking up” the nervous system so the athlete is ready for the work ahead. After that, we need a set of principles to guide how we will structure our training order.

principle of fatigability

Simply put, exercises that require higher neuromuscular output and physical readiness are more susceptible to performance detriments due to fatigue. These exercises are better performed at the beginning of a training session (after warm-ups) when the athlete is fresh and has all of their physical and mental resources. Max effort, max intent modalities like intensive plyometrics, high effort compound lifts and ballistics all fall under this category.

Contrastingly, exercises that require a lesser degree of neuromuscular output like accessory lifts, isolation lifts and stability training can be trained at the end of a session with little to no detrimental effects on training adaptations. If we use this principle to guide exercise order, this is what a typical concurrent power and strength training session might look like:

The same principle can be used if we were train both martial arts and S&C within the same day. Because of the importance of skills training, I would schedule it first. Pre-fatigue can be a tool to improve skill retention and transfer, but in most cases, only hampers skill acquisition and development by making it harder for combat athletes to participate in high quality, deliberate training.

PRIORITY

Prioritization is an exception to the principle of fatigability. An athlete should first perform exercises that are most important to their primary training goal (if they one that is clear-cut). Going back to our athlete is differing athletic profiles, a force-deficient athlete should focus on high-force producing exercises first thing in each training session in order to reap in the most training benefits. Likewise, a velocity-deficient athlete should perform high-velocity exercises before slower movements (the outcome is in line with the principle of fatigability but for different reasons).

Post-activation potentiation and contrast training

Post-activation-potentiation (PAP) is a phenomenon where rate of force development (RFD)/power is increased due to previous near-maximum neuromuscular excitations. This is another exception to the principles of priority and fatigability, whereby the athlete will deliberately perform heavy compound lifts first even if RFD/power is the primary goal.

I’ve written an article about this topic of within-session planning, covering these principles more in-depth. If you’d like to learn more, read “Exercise Order - Principles For Sequencing A Training Session”.

WRAPPING IT UP

Whenever I create an S&C program for combat sport athletes, I’m always considering all 4 layers of programming. Some of the specific methods I use like type of training-split or the type of volume/intensity undulating I use will change based on the athlete I’m working with, however, most of the governing philosophies (on the macrocyclic level - see Part 1) stay more or less the same.

It’s important for S&C coaches to adapt to information given in front of us, not be limited by scientific dogma, but at the same time, be willing to change and improve our philosophies over time. Since combat sports is a growing industry, so is S&C for combat sports. We must navigate through performance training with nuance.

The learning doesn’t stop there. Here are some combat sports S&C articles that will help you along the way.

Squats vs. Trapbar Deadlift, Hypertrophy Training and Plyometrics - Combat Sports S&C Q&A #2

This week’s topics discuss the differences between squats and trapbar deadlifts in a training program, the use of a “hypertrophy phase” for combat athletes as well as how to introduce plyometrics in a fighter’s training.

These questions were taken from my Instagram Story Q&A (@gcptraining). Alongside answering questions on Instagram, I will pick the best 3 questions related to combat sports S&C and discuss them in-depth. Some of these questions were asked by followers and readers of my newest ebook “The Strength & Conditioning Handbook for Combat Sports”.

Question #1 - What is the difference between squats and trapbar deadlifts? They both have similar joint angles.

To the naked eye, they have similar joint angles - especially if you’re using the high handles of a trap bar, meaning you’re “sitting” much deeper into the deadlift. Even if this is the case, squats should have a much larger degree of knee flexion, stimulating more of the distal quadriceps and lower leg muscles.

In terms of programming, there are distinct scenarios where I would use one over the other.

The trapbar deadlift is one of the exercises in the weight room that allows an athlete to lift the most weight. Because of this, I use this to build systemic, full-body strength through high-intensity loads. Although the degree of knee flexion is larger than other variations like the conventional or Romanian deadlift, an emphasis is still being put on the muscles of the mid- and lower-back. Trapbar deadlifts play a big role in improving “pulling-strength” in my combat sport athletes.

In contrast, when I want to build more robust knees and lower-body “pushing-strength”, I prescribe squats. Front squats, safety bar squats, back squats, heels-elevated cyclist squats; any variation that I can load safely and effectively with my athletes and achieve the deep knee flexion angles we want to see in order to develop quad strength.

QUESTION #2 - How would you structure hypertrophy phase while doing MMA?

I wouldn’t. Muscle hypertrophy is rarely a training goal for combat athletes, unless they’re trying to move up a weight class and even then, that is better performed over the span of several months or years, not through a 8 or 12 week phase.

If you find yourself in that position, the best options are to slowly increase the training volume of compound lifts and increase caloric intake over time. The key here is a gradual increase over the span of several training cycles. This way, the muscle soreness from sharp increases in resistance training volume will not disrupt skills training. As well, this gives time for the athlete to become acclimated to their increasing bodyweight.

There are more benefits to a high volume training phase than just hypertrophy.

Increased muscle coordination via repetition volume

Re-sensitization to high-intensity training

Muscular endurance and work capacity

Pair this with proper fueling and let hypertrophy be a by-product.

Question #3 - How would you start with plyometrics for a fighter that’s never done plyometric training before?

For lower body plyometrics like jumps and hops, start with “extensive” plyometrics. Also known as low level plyometrics. Simple exercises like plyometric pogo hops can be prescribed to help the fighter familiarize themselves with redirecting energy/force before moving onto more intensive plyometrics like depth jumps and lateral bounding.

Because extensive/low-level plyometrics are lower impact, they can be trained with relatively high volumes which in turn, will develop favourable tendon and muscle properties that will aid in getting the most out of intensive plyometrics.

For the upper body, exercises like assisted plyometric push ups as well as continuous medicine ball slams are a good choice.

FREE EBOOK CHAPTER DOWNLOAD!

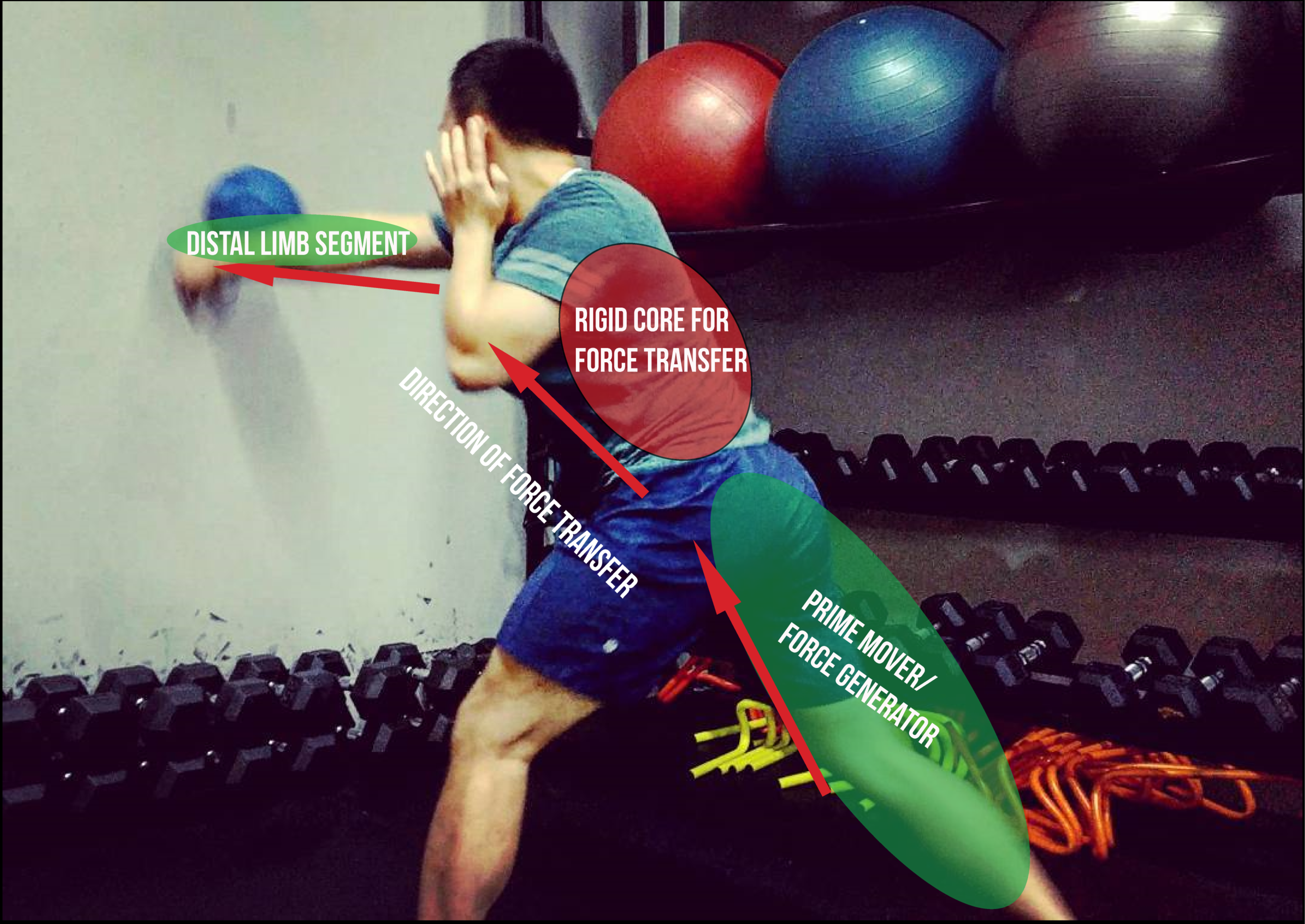

Chapter 7 of the eBook, “The Sport-Specific Trap - Revisiting Dynamic Correspondence for Combat Sports” talks about key concepts to consider when selecting exercises to enhance combat sports performance and some common mistakes coaches make.

MMA Strength and Conditioning: Endurance and Energy System Training for MMA (Part 2)

In this series, I talk about everything related to strength & conditioning and training in the sport of MMA.

WRITE BETTER PROGRAMS WITH THIS FREE CHAPTER

Chapter 7 of the eBook, “The Sport-Specific Trap - Revisiting Dynamic Correspondence for Combat Sports” talks about key concepts to consider when selecting exercises to enhance combat sports performance and some common mistakes coaches make.

read PART 1 here

Part 2: endurance and metabolic demands of mma

In this part of the series, I will give you guys an overview of the body's energy systems, discuss the metabolic needs of an MMA fighter, and then lay out different training methods to improve endurance specific to MMA.

Energy system overview

Strikes, takedowns, grappling, submissions. A wide variety of physical capabilities and a diverse range of martial arts skills are required to excel in the sport of MMA. Don't forget the power and the endurance needed to pull off fight-finishing techniques or to last the whole duration of the fight. We are capable of all these movements thanks to our 3 energy systems: aerobic system, anaerobic system and alactic/phosphogen system. The intensity and duration of our movements is what dictates which energy systems are used, and which substrates are used to fuel that energy system. Each energy system takes a different substrate (fuel) to create energy molecules called ATP (energy currency of our body) that is then used to contract our muscles so we can move. As you can imagine, the energy demands of a sprinter and marathoner have completely different energy demands.

3 energy systems are used in the human body: Aerobic, Anaerobic and Alactic.

The AEROBIC system (also known as the oxidative system) is the slowest acting energy system in our body, yet it is capable of creating the most energy. At rest, around 65-70% of your energy comes from the utilization of fat, 25-30% comes from carbohydrates, while less than 5-10% comes from amino acids (protein). As intensity increases, these percentages shift - carbohydrates become more important because of its quicker availability in the body. That's why you need adequate blood sugar (carb) levels when exercising or doing intensive activity. The aerobic energy system is the predominant system involved in exercise lasting 2-3 minutes, to hours and even days. The aerobic system (aero meaning air) requires oxygen to utilize fat stores (body fat) and carbohydrate stores (in your muscles and liver).

The ANAEROBIC system (aka the glycolytic system), is a faster acting system that can produce ATP even in the absence of oxygen. The downside to this faster ATP-production rate is that it can only breakdown carbohydrates as fuel and it creates a significant amount of lactate (commonly known as lactic acid). Lactate is correlated with exercise and performance fatigue, but the concept is often misinterpreted in the MMA and strength & conditioning world (more on this later). Exercise bouts of moderate to high intensities, lasting upwards to 2-3 minutes are mainly fueled by the anaerobic energy system.

The ALACTIC system (aka the phosphagen or phosphocreatine system) is the energy system capable of producing the most energy within the shortest amount of time. A fight-ending flurry or combination uses this energy system. The alactic system is different to the aerobic and anaerobic system in that it produces energy by directly breaking down the ATP molecule, bypassing the conversion of fats, carbohydrates or protein into ATP. However, our body has limited stores of ATP, therefore the alactic system is the quickest to fatigue and can only produce large bursts of energy for up to 10 seconds. Fully restoring phosphocreatine and ATP stores takes around 5-8 minutes; this restoration time can be influenced by strength & conditioning training, as well as the level of development of the aerobic and anaerobic system.

One misconception about energy systems is that each energy system completely turns on or off during various intensities and durations of exercise. Instead, all three energy systems contribute to energy production during all modalities and intensities of exercise. The relative contributions of each will depend on the velocity and force demands of the exercise bout or sport.

Another misconception is that the aerobic energy system is not used during mixed-type and pure anaerobic sports, when in reality the aerobic system can supply anywhere from 30 to 65% of the energy used in an exercise bout lasting up 2 minutes (800m running event for example).

Endurance and metabolic demands of mma

Professional fights are 3 x 5 minute rounds with 1 minute rest in between rounds and Championship bouts are 5 x 5 minute rounds with 1 minute rest in between rounds. Amateur fights are slightly shorter, generally 3 x 3 minutes or less. A 15 minute or 25 minute fight then, requires a full spectrum of endurance capabilities. A respectable aerobic energy system must be developed to last the whole duration of the fight, while the short, repeated bursts of high-intensity action require a degree of anaerobic capacity and neuromuscular-alactic power.

It's widely known that fights often end before their allotted time limit, either via a knockout (KO) or technical knockout (TKO) by strikes, or by submission (SUB). This differs from other sports such as hockey or basketball where the players are required to play the whole length of the game. In MMA, fighters have the unique ability to control how long the fight lasts. This has huge implications on training strategies as well as damage and concussion mitigation. A fighter could technically never train their conditioning and achieve all their MMA wins by first round knockout... But... we all know that strategy does NOT work against equally-skilled opponents; even the most brutal knockout artists can be taken into deep waters. Professional MMA fighters must have the appropriate amount of conditioning to last at a minimum, 15 minutes. Failing to do so will prevent you from competing at the highest level of the sport.

Let's dive into the details.

MMA consists of intermittent bouts of high-intensity actions, followed by periods of moderate to low-intensity movement or disengagement. By compiling data from other combat sports, Lachlan et al (2016) categorized the metabolic demands based on 2 categories, grappling-based demands and striking-based demands.

Grappling-based sports like judo and wrestling appear to have a work-rest-ratio of approximately 3:1 with work phases lasting an average of 35 seconds, while striking-based sports like kickboxing and Muay Thai have a work-to-rest ratio ranging from 2:3 and 1:2, with work phases lasting around 7 seconds on average. MMA sits in-between these values, with a work-to-rest ratio between 1:2 and 1:4 with work phases lasting 6-14 seconds, which are then separated by low-intensity efforts of 15-36 seconds.

Work-to-rest ratios describe the amount of time exerting energy vs. the amount of the time disengaging and "taking the foot off the gas pedal". The more intense and long the work is, the more rest is needed to restore energy.

It should be noted that the structure of a typical professional MMA bout has a true work-to-complete rest ratio of 5:1 (5 minute rounds, 1 minute breaks), while the work-to-active rest ratio inside each 5 minute round is determined by the tactical strategies and the skill set of the MMA athletes. Fighters described as "grinders" such as Michael Bisping or Nick Diaz will display a much higher work-rest ratio than more "explosive" athletes like Jose Aldo or Tyron Woodley.

There is clearly a tradeoff between power/explosivity (lol Dada 5000) and the ability to perform optimally for the whole duration of the bout.

The best fighters in the world like Demetrious Johnson or GSP are not only in peak physical performance in terms of power and endurance, but have a high enough fight IQ to determine when to engage or disengage during a fight, when to perform a fight finishing flurry, or when to back off.

debunking conditioning myths in mma

"MMA matches only last 15-25 minutes, therefore high intensity interval training is the only way to improve endurance and conditioning"

The most common training mistake amongst fighters. In order to build elite level conditioning, fighters must have a solid aerobic base with a well-developed capacity for anaerobic efforts. As I mentioned earlier, the aerobic energy system is responsible for re-synthesizing ATP after periods of high intensity bursts, therefore influences how fighters recover in-between rounds AND in-between fighting exchanges. Since the aerobic system is developed through low-intensity cardio training, many coaches and fighters overlook this critical piece because it is, incorrectly, seen as inefficient. Oddly, fighters will perform an unnecessary amount of high intensity training along with their MMA training; a recipe for overtraining, sub-optimal recovery and increased risk of injury.

There are multiple contrasting studies on whether the addition of more frequent high intensity endurance training yielded any performance improvements. Some researchers found athletes that don't respond well to high volume low-intensity training showed greater improvements when they increased their frequency and volume of high intensity training. However on the contrary, the benefits of performing more high intensity training in already well-trained athletes, are limited.

What seems to be more important is the sparing use of these high intensity intervals outside of MMA training. By the way of training periodization, and the principle of specificity, the majority of the high intensity intervals should be performed few weeks out before the fight. Performing a high volume of high intensity training year round hinders a fighter's ability to improve their skills and stay injury-free.

Less is more sometimes.

"Being inefficient with your energy in the cage/octagon results in lactic acid build up in your muscles, causing a fighter to gas"

There's definitely some truth to this statement. When fighters "blow their wad" (a la Shane Carwin vs. Brock Lesnar), they're unable to recover, even with the 1 minute break in-between rounds. Why?

During moderate to high intensities, lactic acid and hydrogen ions begin to accumulate as the supply of oxygen does not match the demands of the working muscles - this is the byproduct of the anaerobic energy system. However, another byproduct of this energy system is lactate (mistakenly called lactic acid by the general population). Lactate is closely correlated with fatigue, however: correlation does not imply causation. Lactate is the 4th type of fuel that can be used to restore energy, primarily happening within the mitochondria of cells - the same location aerobic metabolism takes place.

Another common myth is that lactate doesn't form until you perform high-intensity exercises. Lactate actually forms even during lower intensity exercise (because the anaerobic system is still active to a degree). The amount of lactate produced is very minimal; we are able to shuttle this lactate into our mitochondria via the Cori-Cycle and effectively reuse it as energy. During the later round of a intense brawl however, the rate of lactate clearance simply cannot match the rate of which it is produced, this is called the lactate threshold. The figure below shows how lactate is recycled as energy after being produced as a by-product of fast glycoglysis (anaerobic metabolism).

The lactate threshold also represents the switch from using predominantly aerobic metabolism, to anaerobic metabolism. This is where the mental toughness and resilience of a fighter becomes more important. The fighters with the ability to push through the pain while maintaining their martial arts technique, will likely be the winner. In order to effectively delay the onset of muscular and mental fatigue, the goal of every fight should be to increase their lactate threshold.

While a well-developed aerobic base is needed, specifically training around lactate threshold is what will most effectively increase a fighter's ability to perform anaerobic work.

"That fighter has a lot of muscle mass and looks jacked, he will definitely gas out or probably has poor cardio!"

Holding a massive amount of muscle mass can negatively affect endurance, but not always. More often than not, jacked fighters possess poor conditioning due to a combination of poor energy utilization/strategy during fights, and neglecting lower intensity work in the off-season or fight camp. Fighters that put on muscle quickly most likely have focused too much of their time on hypertrophic training methods like heavy squats, deadlifts, presses, etc.

Each muscle is covered by capillaries that provide it blood and energy. Fighters that neglect endurance work crucial for increasing mitochondria density and capillarization of these muscles will have poor conditioning. Muscle mass and elite level conditioning are not mutually exclusive. Fighters who have focused on increasing muscle mass over the long-term while concurrently using training methods to increase capillarization will achieve the best results.

Fun fact: Yoel Romero (despite the blatant cheating) who looks like a Greek god, has 5 third round finishes in the UFC. Fans are quick to point the finger at jacked fighters and call them out for having poor conditioning when it's not always the case.

TRAINING variables & METHODS FOR IMPROVING ENDURANCE IN MMA

Training Variables

Conditioning work outside the MMA skills training revolves around the principles of intensity, volume and frequency.

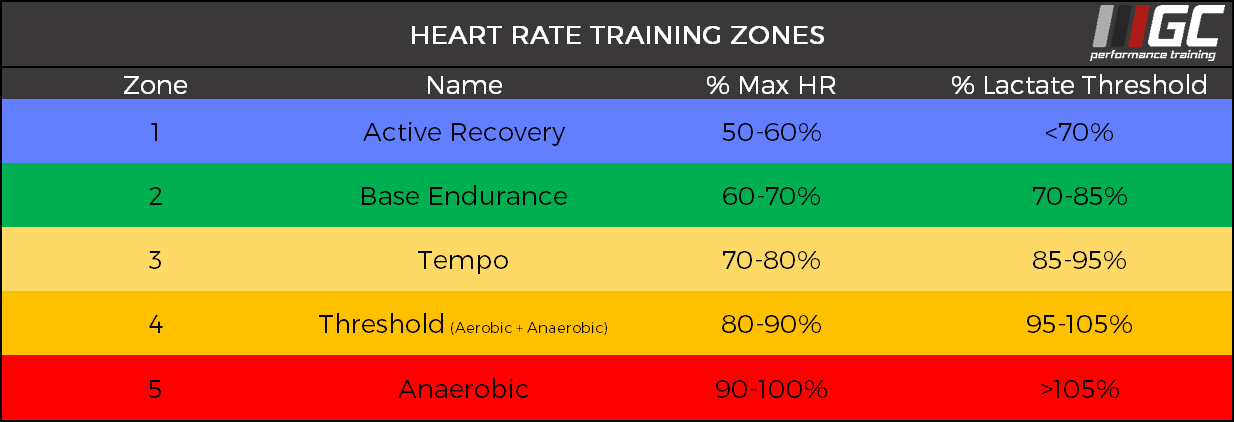

Intensity represents how hard or how close to maximal effort one is working. Maximal heart rate, lactate threshold, rate of perceived exertion (RPE) and power output can all be used to gauge endurance training intensity. Prescription of low, moderate and high intensity workouts are based on a percentage of these baseline or max values.

To make things simplier, intensity can be categorized into different training zones. In the chart below, training intensity zones are based off of a percentage of an athlete's maximal heart rate OR a percentage of their lactate threshold. Heart rate is well-known to have a linear relationship with exercise intensity, in that when workload or intensity increases, heart rate will also increase to supply the working muscles with blood.

Since lactate threshold represents the switch from aerobic to anaerobic energy production, using an athlete's lactate threshold is a more accurate method of prescribing conditioning work. For amateur fighters that may not have the access to equipment necessary to measure lactate threshold, heart rate is the next best option.

Volume indicates how much total work is being put into endurance training. In sports like running, cycling and swimming, volume will be represented by the total distance travelled during training. In team sports and sports like MMA, training volume is measured by using the "time in zone" method. How much time per training day or training week are we spending in each training zone? This will give us an idea on how much rest an athlete needs, or whether we need to push them harder to achieve the level of conditioning we're seeking.

Lastly, frequency indicates how often we are performing endurance training. Specifically, how many times a week we use a specific training method.

Breaking Down The Training Zones

Low Intensity

Zone 1 is commonly called warm-up or active recovery. This intensity is not hard enough for any surmountable enudrance to be developed, but enough to promote blood flow and therefore recovery to the working muscles. Training in Zone 1 primarily uses fatty acids for energy production.

Zone 2 is called base endurance or extensive endurance training. This represents the lower limits of the aerobic energy system and still uses predominantly fat as fuel. Training in this zone will promote higher cardiac output (heart pumps more blood), as well as the capillizarization of muscle fibres I talked about earlier.

Zone 3 is called tempo training or intensive endurance training. This zone challenges the upper limits of the aerobic system. Lactate production starts to ramp up at this Zone, however, there is no significant accumulation as intensity is still relatively low and clearance levels are still high due to the adequate of supply of oxygen to the muscles.

Moderate Intensity

Zone 4 is called threshold training. As the name implies, this training zone occurs near an athlete's lactate threshold (95-105% of lactate threshold). This intensity cannot be held for long, as hydrogen ions begin to accumulate. For this reason, training in this zone will improve an athlete's tolerance to pain/the burning sensation and will directly increase their ability to produce force and energy during muscle and mental fatigue.

High Intensity

Zone 5 often called anaerobic or VO2 max training, is considered true high intensity training. Training in Zone 5 is responsible for increasing an athlete's ability to produce force in a metabolically acidic environment. Paired with the large amounts of perceived exertion, the duration of which this intensity can be held is severly limited compared to lower and moderate intensity training.

Time In Zone

As alluded to earlier, the time in zone method is used to assess training volume. These are training times specific to improving an MMA fighter's conditioning

Zone 1 (Active Recovery) - Any where from 30-60 minutes to promote blood flow, joint flexilibility, muscle recovery. Multiple times a week, pre or post MMA training.

Zone 2 (Base Endurance) - 45-90+ minutes to improve the lower end of the aerobic energy system, increase muscle capillarization, improve aerobic enzymes, etc. 3-4 times a week.

Zone 3 (Tempo) - 30-60+ minutes to improve the higher end of the aerobic energy system. 2-3 times a week.

Zone 4 (Threshold) - 20-40+ minutes to increase lactate threshold and increase tolerance to muscle and mental fatigue. 1-2 times a week.

Zone 5 (Anaerobic) - 10-20 minutes in the form of high intensity intervals (work rest, work rest, repeat) to improve top end work capacity and power. Work intervals in this zone can last anywhere from 10 seconds to 90 seconds. 1-2 times a week.

PRactical training methods

Example Max Heart Rate: 200 BPM

Example Lactate Threshold: 165 BPM

Because I know my own lactate threshold, I'm basing my training zones off of that number.

Improving The Aerobic Energy System (60 minute workout - Low Intensity)

General Workout - 60 minutes total in Zone 2

Freestyle Swimming (20 minutes @ 115-140 BPM) *I like to aim for the middle of these ranges

Versa Climber (20 minutes @ 115-140 BPM)

Stationary Bike (20 minutes @ 115-140 BPM)

MMA Specific Workout - 60 minutes total in Zone 2 and 3

Shadow Kickboxing (15 minutes @ Zone 3 (141-150 BPM))

Skip Rope (15 minutes @ Zone 2 (115-140 BPM))

Takedown/Sprawl Drills (15 minutes @ Zone 3)

Rowing Machine (15 minutes @ Zone 2)

In both workouts, I'm using the most underutilized form of low intensity training - low intensity circuits. Instead of picking only 1 modality, let's say running, we're able to change the stimulus and muscles worked by switching exercises every 15-20 minutes. As long as we keep our heart rate in Zone 2, aerobic adaptations will be made. If we to only choose running, the endurance of our shoulders and arms would be neglected - not ideal for an MMA fighter.

The general workout is considered "general" because of it's lack of MMA-specific exercises. However, this is completely acceptable to do in the off-season. The MMA-specific workout can be utilized when a fighter comes closer to fight night. This shift from general to specific training is often seen in a well-designed, periodized training program.

Improving Lactate Threshold (30 minute workout - Moderate Intensity)

General Workout - 30 minutes total in Zone 4

Airdyne/Assault bike (10 minutes @ Zone 4 (156-173 BPM))

Active Rest - 2.5-5 minutes @ Zone 1-2

Versaclimber (10 minutes @ Zone 4)

Active Rest - 2.5-5 minutes @ Zone 1-2

Rowing Machine (10 minutes @ Zone 4)

MMA-Specific Workout - 30 minutes total in Zone 4

Heavybag Stand-up Work (10 minutes @ Zone 4 (156-173BPM))

Active Rest - 2.5-5 minutes @ Zone 1-2

Partner Grappling/Clinch Drills (10 minutes @ Zone 4)

Active Rest - 2.5 - 5 minutes @ Zone 1-2

Heavybag Ground n Pound (10 minutes @ Zone 4)

Threshold training can be done continuously, but because of the reasons stated above, I like switching it up and using a circuit style of training.

The name of the game here is pacing. It is easy to go a bit too hard on the heavybag or with grappling drills. Have a training partner monitor your heart rate so you stay in Zone 4.

Improving Top End Anaerobic Power (Multiple Intervals @ High Intensity)

General Workout

Hill Sprints or Prowler Push (4 x 20 second work: 2 minute complete rest) (1:6 work-rest ratio)

Active Rest - 5 minutes @ Zone 1-2

Airdyne/Assault Bike (4 x 60 second work: 2 minute complete rest) (1:2 work-rest ratio)

Cooldown - 5-10 minutes @ Zone 1

MMA-Specific Workout

Heavybag All-Out Combinations (4 x 20 second work: 2 minute complete rest) (1:6 work-rest ratio)

Active Rest , Footwork - 5 minutes @ Zone 1-2

Heavybag Takedowns into Ground n Pound (4 x 60 second work: 2 minute complete rest) (1:2 work-rest ratio)

Cooldown - 5-10 minutes @ Zone 1

A wide variety of exercises could be used here. Get creative with your general and MMA-specific drills. The focus here is to work at 85-100% of maximal effort, and getting in a few minutes of complete rest. Power, explosion and the ability to end fights quickly is built here.

![Combat Sports Strength and Conditioning - Microcycle & Within-Session Programming [Part 2 of Programming Layers Series]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1605708338077-FWV40X4D3O675XD8QX5Q/Shared+from+Lightroom+mobile.jpg)

![Combat Sports Strength and Conditioning : Macrocycle & Mesocycle Planning [PART 1 of Programming Layers Series]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1605110722911-P7CE6O4VILYCVBEJ9R58/muay-thai-jump-rope.jpg)

![[Fight Camp Conditioning Guest Post] Bridging The Gap: Conditioning For Combat Sports](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1585917228624-NZJGW93SQK2P6F890J2A/New+article+title+pic.jpg)